IDTMC 3

‘I drank too much caffeine’. Newsletter of things I’ve been thinking about and reading

How can we know what is true?

Let’s start with the question : how can we know what is true?

One way that is commonly misconstrued as the ‘scientific method’ is inductivism. We go out into the world, and derive truths about the future from what we’ve observed in the past. The sun has risen every day hence we infer those patterns will continue. We then come up with theories/conjectures based on those observations.

There are a whole host of problems with this.

The Problem of Induction

The first is the problem of induction. No matter how many confirming observations we make, we cannot logically conclude a universal truth. For example : if we start of with the conjecture : “All swans are white”. We can observe millions of swans, but no matter how many confirming instances we observe, that statement can never be proven entirely true.

A single instance of a black swan would immediately disprove that, no matter how much ’evidence’ you’ve accumulated. This is the problem with Bayesianism - according to Bayesians, you have the most confidence in your theory the more white swans you observe. The day before you find a black swan, you’re the most confident you’ve ever been that all swans are white.

TLDR : We cannot logically derive a universal statement from any finite number of observations.

Popper’s alternative : Falsification and fallibilism

what is the alternative? Popper reconceptualised science as moving away from ‘proof’ and instead towards disproving. We cannot prove the statement ‘All swans are white’, but we can do our best to disprove it. This is falsification. We try to ‘falsify’ statements in science. Popper’s approach is called Fallibilism.

Fallibilism is the philosophical position that all human endeavours, attempts to create knowledge or achieve anything - are subject to error.

All claims are potentially subject to revision or rejection in the light of better explanations, arguments or perspectives. Good scientific theories aren’t necessarily proven true, they’re just not yet falsified - but continue to provide good explanations for the phenomena they address.

On the other hand, the very idea that we are subject to error implies that there is such a thing as being right - that there is truth and that we can find some of this truth. So there is objective truth, and to get closer to it, we go through the process of:

- Conjecture (make a logical consistent creative ‘guess’)

- Subject it to criticism (try to falsify it),

- Either refute the conjecture (get rid of it) or revise it

No matter how many successful ’tests’ a theory passes, there is always the logical possibility that the test could reveal an exception or a limitation. In this world view, all knowledge remains tentative and open to improvement.

David Deutsch and Hard to Vary Explanations

David Deutsch extends Popper’s ideas arguing that the best explanations are those that are “hard to vary” whilst still solving the problem they address. What does this mean?

A theory that can be easily modified to accommodate any new evidence doesn’t really explain anything - its too flexible and arbitrary. Good explanations are tightly constrained by reality and can’t be arbitrarily modified.

Consider two explanations for why the seasons change on Earth

- “The seasons change because of the myth of Persephone and Hades”

- The seasons change because of Earth’s axial tilt as it orbits the sun"

In the Greek myth, seasons exist because when Persephone (daughter of the harvest goddess Demeter) is abducted by Hades to the underworld, her mother plunges the Earth into winter in her grief. When Persephone returns for part of the year, Demeter rejoices and spring returns.

The first explanation is easy to vary - we can change many parts of it arbitrarily to fit. When confronted with the fact that the Southern Hemisphere experiences summer while the Northern Hemisphere experiences winter, a defender of the myth could simply add ad hoc modifications: “Well, Persephone visits different parts of Earth at different times” or “The gods’ influence varies by region.” The explanation can be endlessly adjusted to fit any observation without improving its explanatory power. We can easily ask why Persephone and not someone else.

Take the other theory : the axial tilt theory. This is hard to vary. It explains how the earths axial tilt of 23.5 degrees results in seasons, because at one time in the earths orbit around the sun, one pole will be away from the sun whereas the other will be directed towards the sun. This causes summer in the Northern hemisphere when the North pole is directed towards and the south pole away,

The axial tilt theory, is “hard to vary.” It explains precisely why the hemispheres have opposite seasons, why the tropics don’t experience pronounced seasons, why day length changes with the seasons, and even predicts seasonal changes on other planets. Change any aspect of this explanation, and it no longer works as a coherent system to explain all these phenomena.

Fallibilism in action

Consider a scientist developing a vaccine. She follows the best available research methods, gathers substantial evidence, and creates a vaccine that clinical trials show is 95% effective. The scientific community validates her work, and the vaccine is distributed worldwide.

Two years later, new research techniques reveal unexpected long-term side effects in a small subset of the population with a rare genetic marker. The scientist immediately acknowledges this limitation, collaborates with others to understand the mechanism, and works to develop an improved version.

This scientist embodies fallibilism: she produced valuable knowledge that saved countless lives, while remaining open to evidence that her work was incomplete. The discovery of limitations didn’t invalidate her achievement but created an opportunity for better understanding. The fallibilist perspective allowed her to both confidently act on well-supported knowledge and remain humble enough to recognise and address its limitations when they emerged.

The endless nature of problem solving

The process of problem solving is endless. When we solve something, wee automatically create a whole new set of problems, and they’re usually more deeper and interesting problems than before.

For example : In the 1940s, the development of antibiotics solved the devastating problem of bacterial infections that had plagued humanity for millennia. Penicillin and subsequent antibiotics saved countless lives and transformed medicine.

Yet this solution created new, deeper problems: antibiotic resistance emerged as bacteria evolved defense mechanisms, creating “superbugs” resistant to multiple drugs. This led to more sophisticated questions about bacterial evolution, communication networks between microbes, and the complex microbiome within our bodies.

Scientists now face more nuanced challenges: How can we develop antibiotics that don’t trigger resistance? Should we target bacterial communication systems instead? How do we preserve beneficial bacteria while fighting harmful ones? How might phage therapy or CRISPR-based approaches offer alternatives?

Knowledge as an Infinite Journey

Deutsch emphasises that knowledge creation is potentially infinite. Unlike some philosophical traditions that view knowledge as finite and attainable in full, Deutsch argues that we can make infinite progress toward better explanations.

Each solution we find opens doors to new problems we couldn’t have conceived of before. This isn’t a pessimistic view but an optimistic one - it means human progress need never come to an end. There’s always more to discover, deeper explanations to find, and better solutions to create.

Humans as universal explainers

For some reason, I had this implicit view that humans are not cosmically significant. The universe is indifferent to ‘us’, we are just ‘chemical scum’ on this tiny floating rock. Reading the Beginning of Infinity by David Deutsch, is slowly destroying this idea.

Humans are special, in that they are the only beings we know of capable of generating explanatory knowledge.

David Deutsch calls humans “universal explainers,” meaning that we are unique among all known entities in the universe for our ability to develop theories and explanations about why the universe works the way it does. Unlike animals or computers, which solve specific, narrow problems, humans have the capacity to ask why and create explanatory theories. For example, while a beaver might build a dam instinctively, a human can develop a theory of fluid dynamics or gravity to understand why water behaves as it does.

This explanatory knowledge allows us to do things that a beaver could never do. We can harness energy from building dams, use that to power lightbulbs, the creation of which relies on an entire edifice of good explanatory theories.

Importantly, Deutsch believes that the capacity to generate explanations is limitless and open-ended - hence the ‘infinity’ in the ‘Beginning of Infinity’. Humans can explain any phenomenon in the universe, no matter how abstract or distant, and we can continually refine and improve our theories over time. This process is driven by human creativity, curiosity, and criticism - our ability to test and refine ideas ensures that knowledge grows without bounds.

He destroys bad theories such as inductivism or empiricism. We don’t look for evidence and then come up with theories. We imagine - we dream of ‘distant quasars’ - the theory comes first. This is what he calls a ‘conjecture’. This conjecture can then be refined with criticism (we have to falsify - try and disprove it) and the claim is either refuted or revised.

I’ve naturally been an optimist, but optimism is so deeply built into his world view.

All problems are soluble

He argues that every problem is solvable as long as it doesn’t violate the laws of physics. A problem is occurring because we are not understanding some part of the universe. If we are able to generate good enough explanatory theories, we can solve the problem. For example, for centuries diseases like smallpox were probably thought unstoppable. Until we understood core principles of immunology, we were able to solve that problem. Similarly, today’s ‘unsolvable’ problems e.g. climate change or ageing are inherently solvable. We just need to generate better explanatory theories.

Every problem is a locked door. Humans have the unique ability to invent keys, not just for that door specifically but for any door that might exist.

Homeopathic summary

This is such a diluted summary of everything that is explored in the Beginning of Infinity. Go read the book.

-

Things I’ve been thinking about and reading

Walking and talking

I recently learnt that you can use Siri to append text onto a note without having to unlock your phone. I can just say ‘Siri : Note this’ and whatever I want to record, it automatically saves it onto my ‘Walking Note’.

I’m hiking the Camino de Santiago, and I wanted a distraction free way to jot down notes on the move. Taking out a notebook and writing is one way, but being able to dictate it provides a frictionless experience.

I’m finding I’m typing less overall. Even on the macbook, I installed a local voice model so I don’t have to type anything.

I’ve been thinking about frictionless digital experiences. Can we replicate the feeling of analogue technologies, the single tasking calm energy, with our modern day digital devices? Switching over to voice based interaction seems to be a natural step that helps us in this regard.

Beauty and Truth in the Mundane Occurences

https://www.quantamagazine.org/finding-beauty-and-truth-in-mundane-occurrences-20250509/

My deep and abiding feeling is that if you look at anything closely enough, there will be new riches to be found,” Nagel said.

Deathbed Fallacy

https://www.hjorthjort.xyz/2018/02/21/the-deathbed-fallacy.html

The fallacy is to assume that whoever you are on your deathbed knows how you should live your life right now. They wish they would have done things differently, meaning, they think you should do something differently, right now. You should consider yourself over a lifetime not as a single person, but a line of many people with different views and priorities. Now, do you think the last person in that line is wise and all-knowing?

Trevor Wisecup on WalkieTalkie

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HjuP527Xt2Q

Craig Mod on the Creative Power of Walking

https://lithub.com/craig-mod-on-the-creative-power-of-walking/

When I’m not talking, just walking (which is most of the time), I try to cultivate the most bored state of mind imaginable. A total void of stimulation beyond the immediate environment. My rules: No news, no social media, no podcasts, no music. No “teleporting,” you could say. The phone, the great teleportation device, the great murderer of boredom. And yet, boredom: the great engine of creativity. I now believe with all my heart that it’s only in the crushing silences of boredom—without all that black-mirror dopamine — that you can access your deepest creative wells. And for so many people these days, they’ve never so much as attempted to dip in a ladle, let alone dive down into those uncomfortable waters made accessible through boredom.

For me, from this boredom—this blankness of mind as I walk past sometimes fields and sometimes giant gambling pachinko parlors—words flow. I can’t stop them.

Photo Portfolio : Living Rooms of Notable New Yorkers

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/05/12/power-houses

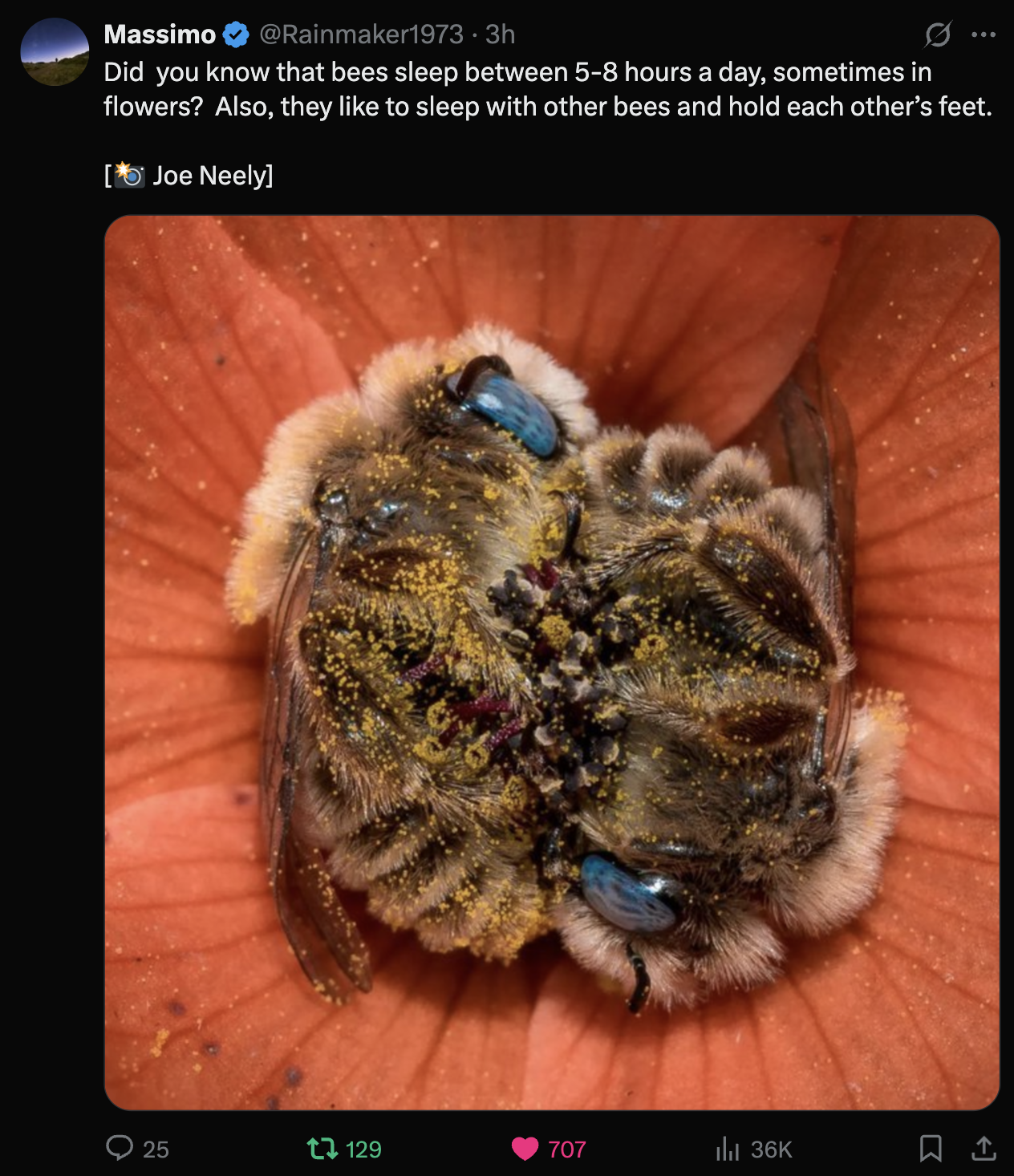

Tweets

Encountering a lot of doomerism and ‘romanticising of the past’. I remember a conversation with a friend who didn’t want to have children because ‘why would I want them to be born into this dying planet etc etc’.

The past was not good, anyone who has read any bit of history knows this. We’ve objectively made scientific progress, moral progress, aesthetic progress. Shutting your eyes to this fact makes me deeply sad - we of course have problems (there will always be problems), but this is the most exciting time to be alive. Go out, pick a problem and devote your life to it.

The only way out is through technology. Being open to the methods of error correction and criticism so that we create better explanations to understand and shape the world. There is no ‘shape ship earth with limited resources’ - there is the universe, and that is our home.

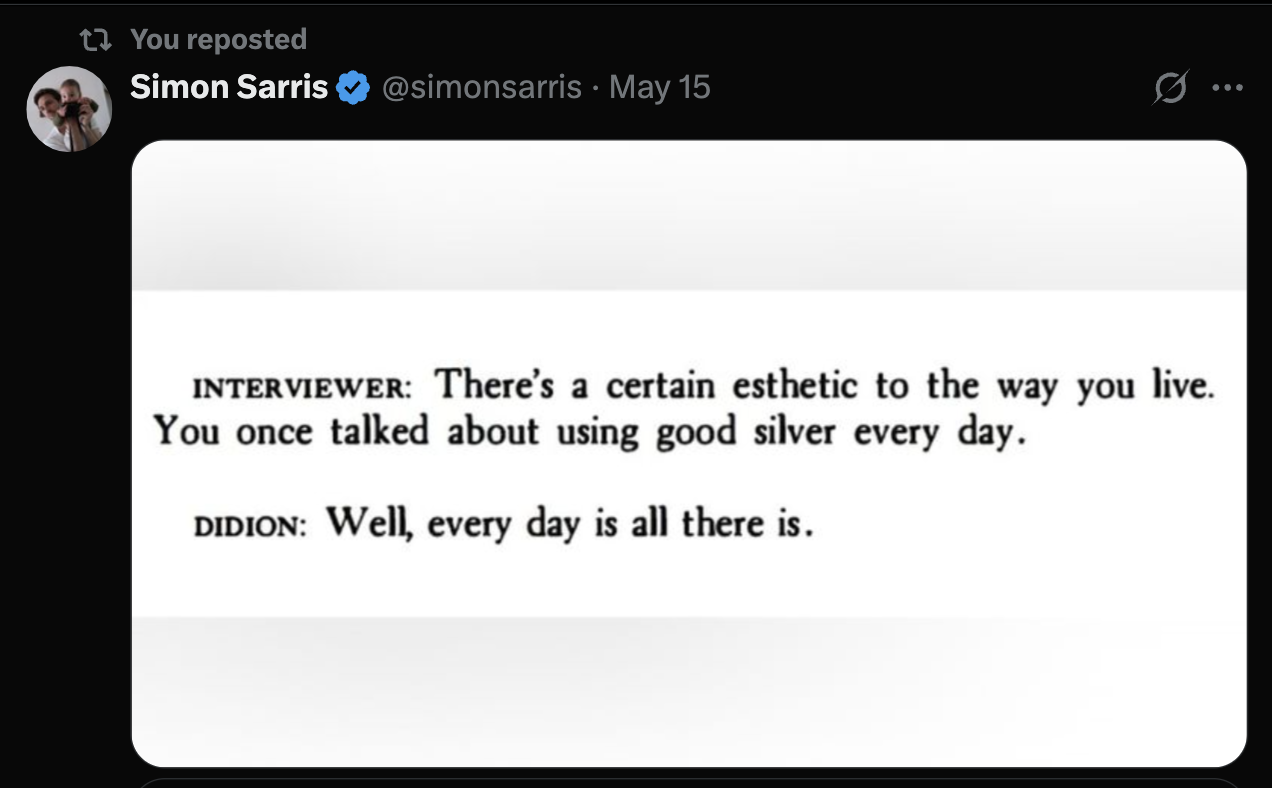

Use your nice things! Every day is all there is

Use your nice things! Every day is all there is

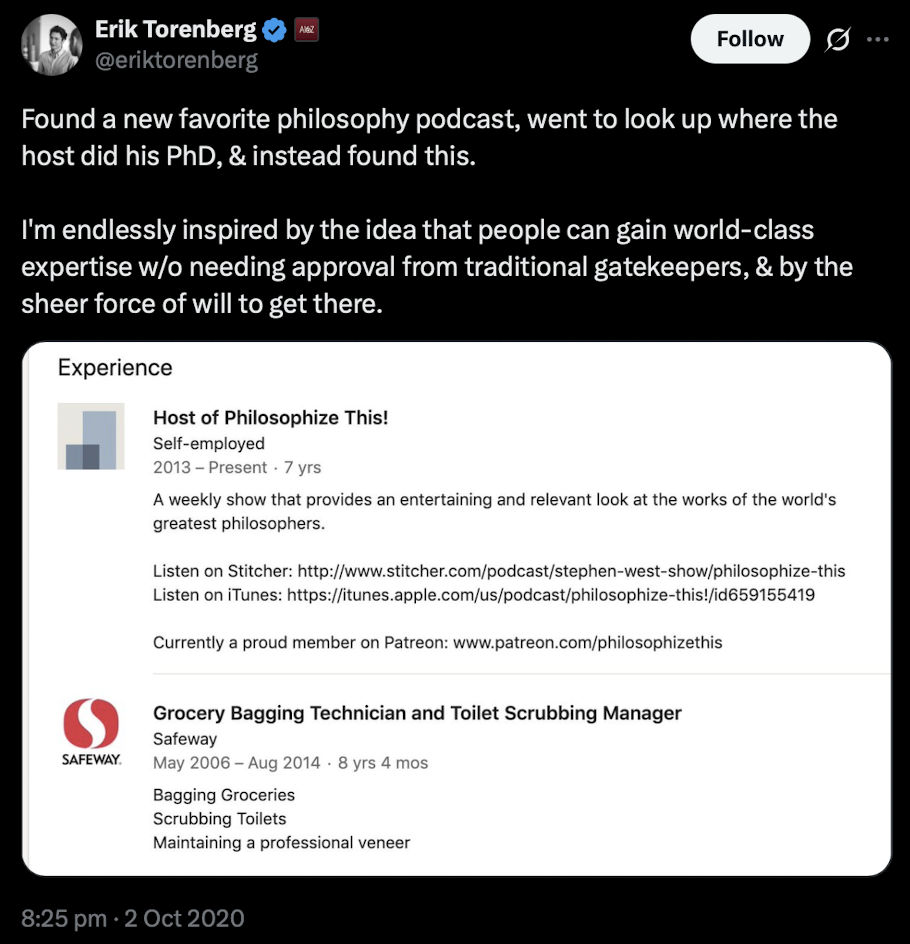

I feel like this is going to become more and more common. Agency is the most vital skill of this age.

I feel like this is going to become more and more common. Agency is the most vital skill of this age.

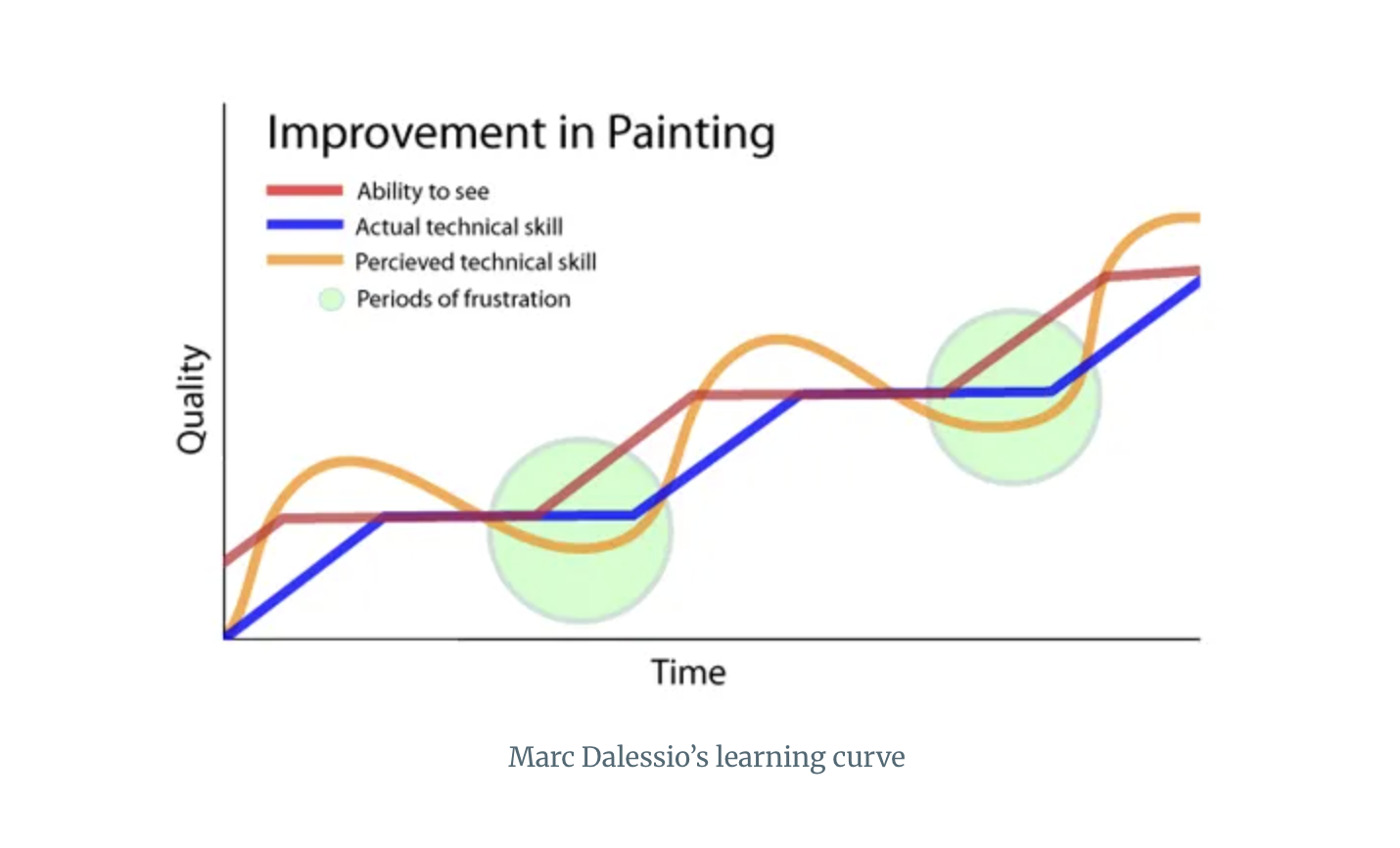

https://stephangiannini.com/2010/12/24/marc-dalessios-learning-curve/

It reminds me of Ira Glass’s ’taste-talent’ gap.

“Nobody tells this to people who are beginners, I wish someone told me. All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you. A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. Most people I know who do interesting, creative work went through years of this. We know our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have. We all go through this. And if you are just starting out or you are still in this phase, you gotta know its normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week you will finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions. And I took longer to figure out how to do this than anyone I’ve ever met. It’s gonna take awhile. It’s normal to take awhile. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.”

― Ira Glass

Reading

- The Best of LessWrong

- https://quarter--mile.com/Human

- https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/14/technology/ai-jobs-radiologists-mayo-clinic.html

- https://wvnl.xyz/hereistoday/

- https://aeon.co/essays/your-brain-does-not-process-information-and-it-is-not-a-computer

- https://www.losethevery.com/

- https://www.hillelwayne.com/post/microscopy/